Cotton Mills of the Jones Falls

Shipbuilding and the Rise and Fall of Sails

The rise of cotton milling in the Jones Falls was the result of a convergence of forces: a ready market for sails from shipbuilders in Baltimore Harbor; proximity to the cotton fields of the American South; cheap labor; and the availability of a cheap energy source — coal — from the mountains of West Virginia via the new Baltimore & Ohio (B&O) Railroad.

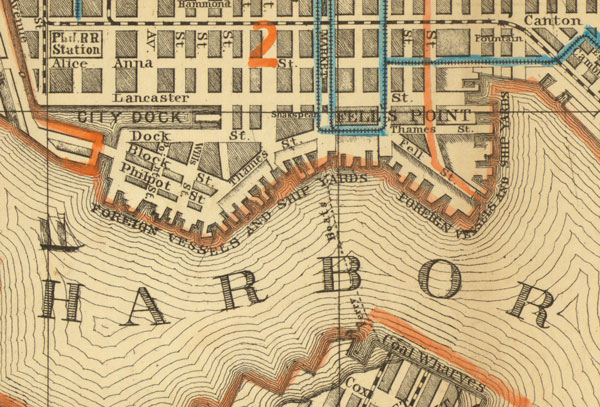

Fells Point shipyards, a section of the “New and Enlarged Map of Baltimore City: Including Waverly, Hampden, All the Parks, and a Miniature Map of the State” by John F. Weishampel, 1872. From the original map at the American Geographical Society Library, University of Wisconsin, Milwaukee.

Baltimore Shipbuilding

The need for ships during and after the Revolution spurred shipbuilding in Baltimore’s Fell’s Point. By 1809 there were 9 shipyards, 11 sail makers, 4 ropewalks and 8 ship chandleries in the area; and about 40% of the population worked in maritime trades. Shipbuilders like Thomas Kemp and William Price became expert at building sleek vessels that were well suited to smuggling, privateering, or any situation where speed, evasion and surprise were important.(“Fast Ships” panel 7)

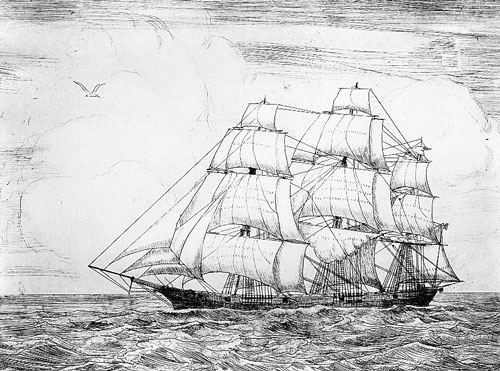

Baltimore Clipper Hornet, right, next to a square-sailed frigate. Note the square sails at the top of the front mast, compared to the main sails, which are attached to the mast at the front and hang free at their back. The square sails are efficient when the wind is from behind, but the clipper’s sails create an airfoil, like an airplane wing, when wind hits the front of the sail, and draws the boat forward. “Enterprise, Pennsylvania, Hornet, South Carolina” by Fred S. Cozzens (1846–1928). Collection University of Baltimore.

Baltimore Clippers

After the Revolutionary War, fast, maneuverable ships were needed to elude the English warships that preyed on American shipping. The design that emerged had a V-shaped hull that could cut quickly through the waves (according to Clark, their hull designs were based on those of French privateers). The British warships had square sails, and so needed to be sailed with the wind; Baltimore Clippers were rigged more like a dingy is today, and were highly efficient sailing into the wind. The result was they could run rings around the British vessels, and run away when they needed to. They were particularly effective as privateers during the War of 1812, capturing over 2,500 British vessels (Petrie 1).

Baltimore Clippers reached their zenith between 1795 and the end of the War of 1812. Once the war was over, the ability to carry cargo became more important than speed, and the clippers, with their narrow, pointy hulls, became obsolete. (“Baltimore Clippers”)

The elder William Hooper would have started in the sail making business supplying English sails to Baltimore Clippers.

Ann McKim, built by Baltimore shipbuilders Kennard & Williamson. Lithograph by E. Armitage McCann, Peabody & Essex Museum, Salem, Massachusetts

Ann McKim

In 1833, Baltimore merchant Isaac McKim commissioned a ship he named for his wife, Ann McKim. It was larger than the earlier Baltimore Clippers, was faster than any European ship of the time, and served in the China and South American trades. Ann McKim is often called the first American clipper ship, but in reality she was a larger, square-sailed version of the Baltimore Clipper ships and had little in common with famous clippers of the 1850s like the Flying Cloud (Clark 60–62).

Though her design did not directly inspire later clipper ship designs, her size and speed did, and pointed the way to large ships with larger sails.

Canvas Sails

As ships built and maintained in Baltimore grew bigger, they called for more and bigger sails. This suggests that there was increasing demand for canvas and sails. Since sails are consumable goods aboard a ship, constantly needing replacement and repair, to be using more and bigger sails suggests that profits from the goods shipped were increasing, the prices of cotton sails were dropping, and/or economies of scale offset the increase cost of the sails.

Illustration of clipper ship Flying Cloud by Jack Spurling, c. 1926, from Sail: Romance of the Clipper Ships, Basil Lubbock, 1972.

Tea Clippers

Tea Clippers (with square sails rather than gaff-rigged like the earlier clippers) sailed all over the world, primarily on the trade routes between the United Kingdom and its colonies in the east; in trans-Atlantic trade; and the New York-to-San Francisco route and New York-to-Sydney around Cape Horn.

“In the early days of the California gold rush ... it took more than 200 days for a ship to travel from New York to San Francisco via Cape Horn — a voyage of more than 16,000 miles. In 1854 the clipper Flying Cloud made the same journey in only 89 days and eight hours — a headline-grabbing world record that was not broken until 1989. At this same time the voyage between Liverpool and Melbourne, a distance of 14,688 nautical miles, was reduced from 100 days to just 64 days.” (“Clipper Ships”)

The boom years of the Clipper Ship era began in 1843 as a result of the growing demand for more rapid delivery of tea from China. This coincides with the rise of the cotton mills of the Jones Falls. The boom continued under the stimulus of the discovery of gold in California and Australia in 1848 and 1851, and ended with the opening of the Suez Canal in 1869. (Clarke vi) The Suez Canal was a huge advantage for steam ships traveling to Asia, and very difficult for sailing ships to navigate. After the opening of the canal, clippers were primarily used to transport immigrants and supplies from England to Australia and New Zealand.

Civil War and After

“During the Civil War [1860–1865] the sailmakers had all the business they could handle, not only making sails for the navy, but also making tents. Following the War, the rise of the oyster business caused the greatest boom in sailmaking the Chesapeake Bay has seen. By 1882, two Baltimore firms were operating two lofts [open rooms where sails were stitched] each.* In addition, there were eighteen firms with at least one loft apiece.” (Brewington, 144)

Steam and the End of Sails

The steam-powered boat was invented in the late 1700s, and Robert Fulton built the first practical steam boats in the early 1800s. The advantages of steam were the same for ships as for cotton mills. Mill wheels are reliant on rainfall; sailing ships are reliant on the wind: neither is predictable. But steam-powered cotton mills and steam ships can run so long as there is coal to run them.

As Tea Clippers set their records sailing the tea routes to China, steam technology was moving relentlessly onward. With the development of the SS Great Britain in 1843, the first iron-hulled, propeller-driven steamship, the fate of the great sailing ships was sealed. Within thirty years, virtually all merchant and military ships had converted to metal hulls and steam power.

Though there was a boom in sailmaking from the Chesapeake oyster fleet in the 1880s, the cotton mills of the Jones Falls were forced to look for new markets for their canvas. New markets included U.S. Army uniforms and tents; bags for picking cotton and carrying coal; and U.S. Mail bags (“Disappointing Duck Trust”). Hooper & Sons also pursued fishing gear such as netting and twine; at one point their letterhead included the tagline: “The Fisherman’s Friend.” (McGrain Scrapbook)

*According to a map of the time, Hooper & Sons had a sail loft in the inner harbor and one in Fells Point.